All organisations produce something, whether it’s either goods or services. The problem is that the production process, whatever it is, even if it’s in the government sector giving out advice, that’s still a process and it’s still providing a service, exposes people to risk.

All organisations produce something, whether it’s either goods or services. The problem is that the production process, whatever it is, even if it’s in the government sector giving out advice, that’s still a process and it’s still providing a service, exposes people to risk.

Most organisations have and need various levels of protection to intervene between the local hazards and their possible victims and lost assets such as the model depicted in diagram 1. Most organisations have something like this in place.

The real problem is that the production process is generally well understood. You have so many machines and we put things in the machines and we get things out the other end. Or you have somebody behind a counter; the more customers that come in, the more sales you make. Or you have people coming and asking for advice and you give advice and at the end of the day you say you saw 15 clients today. That’s production. It’s a production process. It is very easy to understand. You do more of this and you definitely get more of that.

But protection needs are different, they’re much more varied, complex and subtle, and the level of protection really has to match the level of risk in the organisation.

It’s a question of, what is the real level of risk that you are exposed to?

The law says to provide a safe workplace; provide controls commensurate with the level of risk. The problem is that the partnership between production and protection is rarely equal:

- Production produces income (Outputs, whatever is legal currency in your organisation)

- Managers generally come from a production background (They know how it works)

- Information on how to improve production is direct (You make the machine go faster, you get more of something)

- Successful protection is indicated by the absences of losses (Very difficult for the production mind to believe)

- Information on protection is indirect and discontinuous

All rational managers agree on production and protection being equivalent – in the long term. It is in the short term that conflicts arise, and production generally wins.

As production pressures increase, resources are allocated to achieve this without corresponding margins of protection – until an accident occurs!

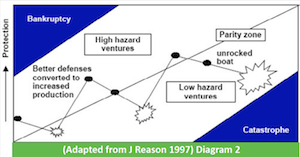

The line in the middle of diagram 2 is a balance between doing the right thing and not doing the right thing. If you go too far down one end you end up in catastrophe. If you spend too much money on protection you go bankrupt. Clearly no one wants to be the safest organisation that ever went out of business. On the other hand you really don’t want to blow the place up and take half the suburb with it either.

So an organisation might start off and say:

“Yep, I have to look after the law, I have to comply, I have to do all the right things, and so I have a good safety system, then we run into the GFC and have to cut costs, orders are down a bit, so we better start trimming some of the systems that we have in place for safety, training, and we’ll postpone replacing that machine”.

Any system that you don’t maintain, degrades, believe or not it’s the second law of thermodynamics. The same happens with relationships. If you don’t maintain them they break up. If you don’t maintain a machine, it goes broke. If you don’t maintain a system it becomes useless.

So over time the system degrades until you have an incident and everybody wakes up. “Whoops, we had an incident, oh! We should have done some more training,” and WorkSafe comes in and says “your training matrix is out of date, and that machine’s certification is out of time,” etc, etc.

Evidence shows that lengthy periods without serious accidents can lead to a steady erosion of protection. It’s easy to forget to fear things that rarely happen. Urgent Vs Important – “there is always something more pressing”. If production increases, then doing nothing on protection is not an option – the safety margins will decrease (think increase with frequency) and neglecting existing defences and failing to provide new ones can lead to catastrophe.

Continue reading Part 3: Defences

Reasons adapted diagram taken from Reason, J.T. (1997). Managing the Risks of Organisational Accidents. Aldershot: Ashgate